by Sam Murray

With my time as an intern for FCCAN coming to an end, I’ve been reflecting on the many experiences and lessons learned this past year. While 2020 was a difficult year for me, as it was for almost everyone, it was also a year of reconnection where I set out to understand who I am in relation to my family and family’s past. It’s bittersweet to know that I am leaving by the end of the summer, having finally formed a connection with this place after living within the insulated bubble of CSU for three years. However, I have so much gratitude for the people I have met and the stories of my family and ancestors that I have uncovered and brought to light. I started my internship with a focus on environmental justice (EJ), spending time with both the Environmental Justice Working Group and the Center for Environmental Justice (CEJ) at CSU. Spending so much of my time researching environmental injustices, brought to mind the proximity that I have to EJ.

I was born to young and poor parents struggling to make it by in rural Kansas. My family moved to Colorado when I was ten, in hopes of a more promising future. Similar to my parents, both my paternal and maternal great grandparents came to the Great Plains in search of opportunity and to escape famine, assimilation, and displacement. My mother is Swedish and Volga German and, from what my Father knows, he is of Irish and Volga German descent. Both families were able to take advantage of the Homestead Act, acquiring stolen land to settle and farm in Kansas, Nebraska, and South Dakota. While digging through my family history I Iearned that my Great Grandfather wanted to immigrate to America because of the shortage of food in Gotland, Sweden. Similarly, my Volga German family came to the States during the turn of the century, escaping famine and the growing anti-German sentiment from the Russian monarchy.

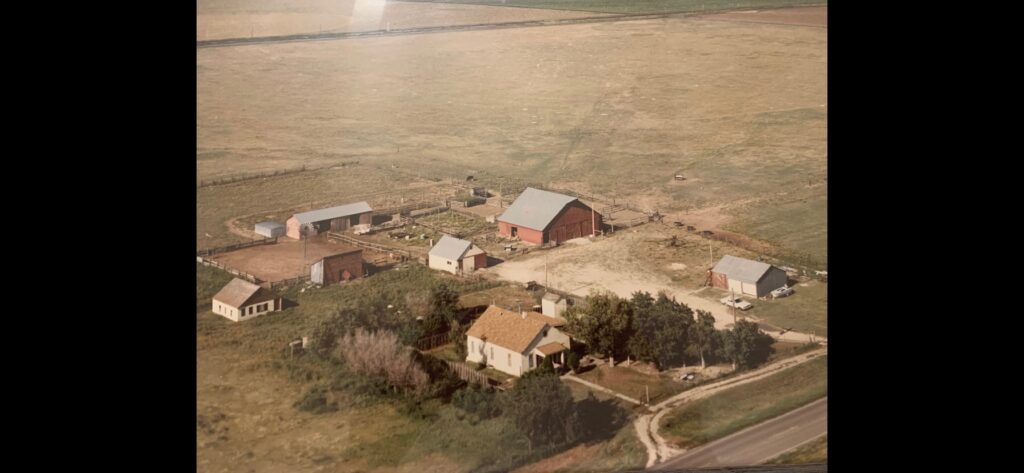

The farm that my dad grew up on

While the Volga Germans were facing increasing conflict, and by the 1920’s would be subjected to genocide, they settled land that lived on by Indigenous peoples. The Russian monarchy had been trying to “civilize” the Volga region and failed multiple times. The Manifesto that brought ethnic Germans and Ukrainian to this region was just another strategy to infringe on the autonomy of the Chuvash, Bashkirs, Kalmyk, Kyrgyz, Mordvins, and Tatars. Similarly, Swedish people of Nordic descent have encroached and stolen traditional Sami land, forced assimilation policies, and instilled anti-Sami sentiment within their society.

While my great grandparents and their families sought refuge in the Great Plains, this opportunity came at a great cost and environmental injustices claimed the lives of most of them, leaving the small family I now have today. Most of my extended family and many of my immediate family have died from rare forms of cancer. Growing up in Kansas, in poor and rural areas, my Great grandparents and Grandparents had farmed wheat, corn, and worked in hog farms. Both my parents remember the green and pink pesticide clouds that would be sprayed over their houses. My Dad recounted that he would be playing outside when the planes would come, and my grandmother would be at the door screaming for him to run back to the house. He would often get stuck in the clouds. Similarly, he remembers the run-off lagoon at the hog farm and the horrifying smell in the air that he said, “stuck to my skin and clothes.”

Here is my mom’s family in Kansas during the dust bowl:

My paternal grandfather and his five siblings all died from cancer in reverse order, with

the youngest, Karen, dying first at the age of 47 from breast cancer. Considered “radical,” Karen

had the most liberal views for their nuclear and conservative family. Which is probably why no

one listened to her when she told everyone that she might have found evidence that their family

was exposed to toxic waste in the 60’s. With so many family members and relatives dying of

cancer, it quickly became normalized and by the time I had turned 12, I remember having gone

to more funerals than family gatherings. Now, as my parents go to check-ups, remove polyps,

and monitor what doctor’s call “high-risk genetics,” I fear that the environmental harms that

have pervaded my lineage will find its way back into our small family’s life again. Which

obviously is to say that it had never even left.

However, the environmental privilege that my living-immediate family holds, is the piece

of this story that I hope leaves with you as a reader. Environmental justice issues are often

intentional and as a direct result of populations marked as “surplus” or “sacrificial”.

White settlers experiencing environmental injustices is not uncommon, for anyone can be impacted by EJ. However, white settlers, like my family, are often able to remove themselves from an environmental justice situation. Or they are able to leverage their privileges and bring to light the EJ issues that is impacting them–and sometimes even before it does impact them (i.e. DAPL was originally planned underneath Bismarck, ND). My family can serve as an example where they had enough generational wealth from allotted property, that many could afford medical expenses or move out of the area.

Swedish Tapestry from my parents house

As I have tried to unpack my whiteness over the past four years at CSU, confronting my

familial and personal history with environmental justice has been foundational for me in

reconnecting with who I am. However, as a white settler it is not enough to just know where I come from before my ancestors assimilated into American whiteness, nor how EJ has impacted me. It is essential to understand the environmental privilege that white settlers hold, despite how environmental harms have impacted them. While my family and ancestors directly perpetuated the genocide of Indigenous peoples by settling allotted land, this legacy unmistakably lives on today with me as I am implicated and participate in the ongoing structure of settler colonialism.

My journey to reconnect with my family’s past is continuous, and I realized that I have a great need to reconcile for not only the violence ensued onto my family and the land they were on, but the violence they have perpetuated and benefited from.

I believe there is deep significance in the identities I hold, the histories of my relatives, and the cancer and disease that has taken the lives of so many of my family members. I’m not sure what that significance is, but I hope to transform that significance into something meaningful. Reconnecting and reckoning will be a lifelong process. I hope that now that I am starting the process, I will find the answers and connections I am searching for. Until then, I am thankful for the family that I have, the family that I have chosen, and the friendships that ground me.