By: Jovan Lovato

Colorado State University recently unveiled a university-wide statement to acknowledge the Indigenous peoples of this land. The statement is to be read at all major university events, and, indeed, I have heard it many times over in the past year. It was drafted by a group including people from CSU’s Native American Cultural Center (NACC), administration, and others from across the campus community. It is difficult to communicate the level to which I value the introduction of this acknowledgement and how painful it is to experience when it is not taken seriously. In the hopes of preventing the abuse of the statement, I want to offer my insight on the experience of land acknowledgement.

My ethnicity was always a big mystery growing up in Fort Collins. I don’t have enough fingers and toes to show how many times I’ve been asked “What’s your ethnicity?” “Where are you from?” or “Are you Mexican?” Ironically, the more I was asked these questions, the more difficult it became for me to answer. There is a rather complicated history behind my families’ cultures and identities. Every time I was asked, I had to confront a series of other unanswered questions inherited from generations of colonization and Americanization. It is simply not possible to communicate all that’s encompassed in my mind, heart, and soul when the expected response is limited to one or two words.

When I first read the university-wide land acknowledgement, I thought to myself “Oh, I’m reading about myself!” Like the land, I need to be acknowledged in all my complicated history. Like the land, people (myself included) have forgotten who I am and need reminding. Like the land, I was Mexicana once, and I am Indigenous always.

So, the land acknowledgement has become an important personal and political experience in recognizing and being recognized.

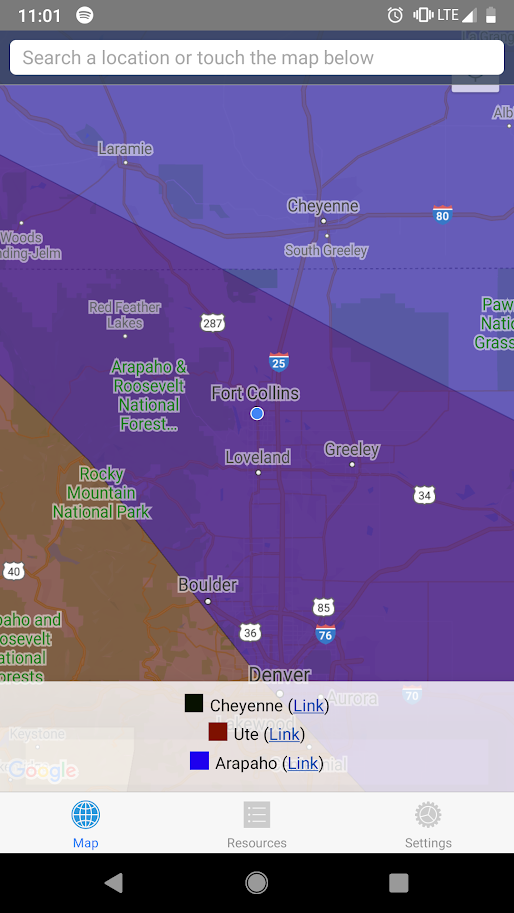

This is not to say that land acknowledgement is not, in fact, about the land or that it’s specifically about me. Displacement of the Ute, Cheyenne, and Arapaho out of Colorado and onto new lands, presumed ownership of land, and “development” of the land should be at the center of this discussion. The land and the people are undeniably connected, however, and, as an Indigenous person, I believe that land acknowledgement is almost just as much about me as it is about all my relations.

For these same reasons, I am deeply troubled and hurt by people who do not seem consider acknowledgement of the land a serious experience. It is not my intention to provide a list of people, organizations, or departments here who I feel have stumbled in their efforts to acknowledge the land and it’s original stewards, but I will provide a few examples. On more than one occasion, I’ve listened as people as paused awkwardly before audibly struggling to pronounce Ute (sometimes coming out like “oot” or “ootay”). It reminds me of when people pause before incorrectly pronouncing my name. I’ve listened as people have read the two paragraphs as quickly as they possibly could as to get to the next item on their program agenda. The message here is clear: “this isn’t really important…”

These actions do have consequences. They are internalized by people like me who are repeatedly taught that our Indigenous histories are unimportant, by non-Native people who don’t think it’s relevant to think about how they came to occupy these lands, by people in positions of power who think that by reading a few paragraphs they have fulfilled their responsibilities to Indigenous peoples and are dismissed from any further action.

Acknowledgement is the fist, easiest, and smallest step in a long and difficult process of decolonization in academia. For that reason, it is arguably one of the most important. We must take it seriously, speak intentionally, and listen carefully. After that, we must continue to act in accordance with the seriousness and urgency necessary to complete the decolonization process. If we are so dismissive of the first step, the second becomes unthinkable.

To conclude, I want to offer a few suggestions. These are for people who are doing an acknowledgement (on or off campus) and who will be listening to one.

- Be prepared. If it has been written for you, read it beforehand! If you have access to it before you attend and event, read it beforehand! Make sure you know the names of the Tribes you’re about to speak.

- Be relevant. Land acknowledgment isn’t directly connected to Indigenous people alone. Every one of us plays a part in the perpetuation of colonization. Try asking yourself how your families and friends came to live where you do currently or what made it possible for you all to be in the United States.

- Be clear. Whether your speaking, signing, or writing, you should be sure that you are taking your time and allowing for the message to be communicated effectively to your audience.

- Be relevant, again. Where a university-wide land acknowledgement comes up short is in regards to specificity. You should take the time to include a few comments on how the acknowledgment is directly connected to whatever the topic of your event is.

- Be thankful. After the acknowledgement and the event, I hope that you practice thankfulness that you’ve had the opportunity reflect on the land and it’s original peoples. I hope that you continue to think about the land as you go on with your daily activities. I hope that your activities shift to include some decolonial work daily.

At the following website and app, you can see whose land you are on at any time. It also provides a brief guide, with more suggestions, on how and why to draft an acknowledgment. I highly suggest you download on your mobile devices! https://native-land.ca/